|

Bassplayer, A life with Fleetwood Mac - John McVie Bassplayer, May-June 1995

A life with Fleetwood Mac - John McVie

By Alexis Sklarevski John McVie has been an integral part of several revolutions in popular music. Born on November 26, 1945, McVie grew up in England. He started playing in a group called the Krewsaders while still in school - and he's never stopped. In the 1960s, he laid down the bottom for the seminal blues-rock band John Mayall & the Bluesbreakers, which paved the way for groups like Cream, Led Zeppelin, and the Jeff Beck Group. Then, in the '70s, he helped Fleetwood Mac to become one of the biggest and most successful pop acts in the world. McVie's approach to the bass may not be considered "technical" or "schooled" - but there's no denying that he can inject more heart and soul into one not than more modern "whiz kids" can summon up on an entire record.

Over the past 30 years, partnered with rock-solid drummer Mick Fleetwood, McVie has provided one stellar bass line after another for an astounding array of Fleetwood Mac hits, such as "Rhiannon", "Say you love me", and "Dreams". I had the opportunity to interview John before the start of a Fleetwood Mac recording session in Hollywood, where the band is preparing to add yet another album to its long and colorful history. What's the new Fleetwood Mac lineup? There are actually two entities right now. There's the road band, with Dave Mason and Billy Burnette on guitar, Bekka Bramlett (Delaney and Bonnie's daughter) on vocals, Mick, and myself. Then there's the recording band, which has (singer/keyboardist) Christine McVie in it. This new band has a little more edge to it, and it's bluesier than before. Bekka's playing is very R&B, Billy is rock & roll and rockabilly, and Dave is... Well, Dave! The combination seems to work really well; I'm very happy with it.

You've been working on the new album for quite a while. We started recording in September1993, with the best intentions to finish it in four months; it was going to be a straight-through project, but we were also going out and doing gigs at the same time. We played Crosby, Stills & Nash 25th Anniversary Tour last summer, we did another little tour that ended, and we also went to Europe last December - so the recording has dragged on a bit. We went in, cut some tracks, stopped to rehearse, and then went out on the CSN tour; that turned out to be the best thing that could have happened, because when we came back our chops were really up. We cut 12 tracks in two weeks! We'd never done that before, which is a good lesson for the future. We've done 19 tunes so far, which we'll cut down to 12 for the record.

How have the shifting lineups affected the band over the years? The first radical change happened when (singer/guitarist) Bob Welch joined the band in 1974; he came from an R&B background, but his writing was very esoteric - we'd never done songs like "Hypnotized" (Mystery to me) and "Bermuda Triangle" (Heroes are hard to find) before. We were always more of a down-to-earth, gut-blues band. When (singer) Stevie Nicks and (singer/guitarist) Lindsey Buckingham joined the next year, we changed again and became more of a vocal "pop" band. We sold a lot of records, although that wasn't a calculated move at all. What caught Mick's attention was Lindsey's guitar playing - the way he could pitch a note and hold it - and also Stevie's voice and her songwriting.

When Stevie and Lindsey joined, did you have any idea how big an influence they would be? Well, I found out at the first rehearsal! After Christine, Stevie and Lindsey sang one song together, it was like, "Oh - this is really good!" It all worked and was just perfect.

What are the good and bad aspects of playing with the same drummer for so long? We know each other's playing really well. Mick knows where I'm going, and I know where he's going, so the song locks - hopefully, anyway. There really isn't a bad side, unless there's something we can't see because we're so close to it.

Is there a way in which you approach working out your bass lines? This is a pet peeve of mine. Before writers had their own home studios, they would come into the studio and say, "I've got a song, and it goes like this" - and they'd bang it out on the piano or guitar. We'd play along with it eyeball to eyeball and go, "Try this… try that," and we'd start working on parts. Now they come in with a DAT that's pretty much the finished version of the tune, with a bass line and everything, and in some cases it's good enough to put on the album. That bothers me, because once an idea for a bass line is in my head, I'm influenced by it; it's hard to get rid of the part the writer recorded and get back to where I can put me into the part. I don't want to just sit there and copy a demo tape. It infuriates me, and I wish people wouldn't do it, even though I guess it's state of the art nowadays.

That sort of ties in with the MTV thing of having to do a video, which I don't care for at all. With videos, the images that go with the track are all predetermined. I enjoy listening to music on the radio, because I like to make up my own pictures to go with what I hear. In keeping with that, I prefer to make up my own bass lines as well.

What do you do when the bass line has already been written? It depends on the song; I'm most conscious of the melody and how it works with the drums. I always try to get in with the kick drum. On "Dreams", for example (Rumours), the best thing Mick and I could do was play sparsely and let the melody carry the song; it demanded that, because it had a lot of air in it. On "Say you love me" (Fleetwood Mac), though, I chose a moving line that flows underneath the vocal and supports it.

The great thing about Mick - and he's the first to say this - is that he's not a technical drummer at all. He's a feel drummer, and a great feel drummer.

What was it like making the Bluesbreakers record with John Mayall and Eric Clapton? It was done at Decca Studios in West Hampstead, England, in less that a month. We played together a lot as a band, so we'd just go in and do takes live, with no overdubs. And as soon as the session was finished, we'd be out to gig.

Eric was, and is, a great player - that's it. After the album came out a strange situation developed, because this upstart guy named Peter Green started playing with John. There were guitar style wars going on between them - all that stuff about "Clapton Is God" being sprayed on the walls was real! In a lot of ways, I think Peter was more of an emotional player than Eric was at the time.

When the record was finished, did you have any idea it would have such a big influence on the direction of rock & roll? No. I mean, we knew it was good, but it's only become a classic with the passage of time. The record was very big among people who liked the blues and were into that scene. At the time, there were definite cliques - people who liked blues, people who liked the Beatles, people who liked this or that - and they tended to be very tight, almost insular about their tastes. That included myself - I got quite snobbish.

At the time, there were three main blues guys in England: John Mayall, Alexis Korner, and a harp player named Cyril Davies, who had a great band. When the American blues players started coming over, Alexis's and Cyril's band would back them up, and when John started to become accepted on the English pub circuit, we began to back the American players too. We played with Sonny Boy Williamson and T-Bone Walker, among others.

I'd like to make the point that John Mayall has not had the credit he deserves for exposing people to the blues. American blues musicians came to Europe and played with us, and through people like John, Alexis, Eric Clapton, and Peter Green, a huge white audience developed. Through this exposure, people would then trace the roots of the music back to the original artists. I believe that John Mayall was fundamental in exposing blues music to the world - and through what happened in Europe, America discovered part of its own culture.

The Bluesbreakers played a lot of cover tunes. Did you try to stay true to the bass lines on the original versions of the songs? I stayed pretty true to the originals, with a few "inflections". I would sit down and figure out the original lines from the records.

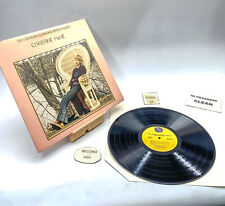

When was Fleetwood Mac formed? Fleetwood Mac first played on August 14, 1967, at the Windsor Jazz Festival. I was the bass player that night; I was playing with John Mayall, who was headlining. Also there was Chicken Shack, with Christine on piano - she was a killer blues pianist, just a phenomenon! In fact, she was Freddie King's pianist of choice; whenever he came to England, he would ask for Christine. But unless you've heard the Chicken Shack records, you've never heard Chris play blues piano. (ed.note: Christine McVie was known as Christine Perfect at the time. She was later married to, and divorced from, John.)

Peter Green was harassing me to join the band, and I said, "No, I'm fine playing with John". At the time John had horn players in the band, and we were rehearsing at some club when John turned to one of them and said, "Okay -just play it free-form there". I said, with typical blues snobbishness, "I thought this was a blues band, not a jazz band!" I immediately went across the street, called Peter, and asked if he still wanted me to join up. I joined Fleetwood Mac in September '67.

Ten years later you released the most successful Fleetwood Mac album, Rumours. What was it like making that record? It's a miracle everyone made it out alive! It was a very self-indulgent time; there was no limit, and no one knew when to say, "That's enough!" For example, there was a week-long period when we were convinced the pianos were out of tune, so we went through nine pianos and seven piano tuners and ended up with one guy we called the "Lunar Tuner"! We never took a day off, unless someone was sick. We'd work all night, and at ten o'clock in the morning, we'd be standing outside a pub waiting for it to open so we could have a nightcap, which would end at two in the afternoon. This went on for two months! It's surprising no one got seriously injured. But we did what was necessary to get through it, and if we had to do it over again, I think we'd do exactly the same thing.

How did you record your bass? Every track was different. On some I recorded direct, and some were a combination of an amp and a direct line. On one track, we combined a direct line and a miked Pignose amp, which was inside an Anvil case! We spent a lot of time on the bass sounds. There was a lot of experimentation going on - putting pads under strings, all kinds of stuff.

Were the songs easy to arrange? It was straight a head, because we knew each other pretty well. It was a "family" band, even though it was a dysfunctional family. The communication was easy, although that became harder later on.

Did you write the famous vamp section at the end of "The Chain" ? All those bass lines are mine - every one. When we played "The Chain" in the studios, I just went into that line at the end. They used that tune in Europe for about ten years as the theme for a Saturday-afternoon motoring program about cars and racing - very weird!

It seems as though you've never had a problem coming up with original lines. No, not really. I butted heads Lindsey a couple times, because he had very fixed ideas; I would say, "Look, this is how I feel it." He was really the only one to do that, though.

Who were your main musical influences? John Mayall, and Willie Dixon, whom John turned me on to. The Bluesbreakers drummer, Hughie Flint, turned me on to Charles Mingus; there seemed to be a great similarity between Mingus and Willie Dixon, in that they were both very lyrical, melodic players. I must have every Mingus record ever made - I'm a big fan. And Paul McCartney is a great player.

Do you listen to any of the younger players now? No - I find myself going back to the old stuff all the time.

Do you still enjoy touring? That's my love. I'd rather be on the road than in the studio, although on the road I miss my family. I love to record, but I can't sit in the studio for 12 or 14 hours - Mick and Chris can do it, but it drives me up the wall.

Did you ever aspire to do sessions outside of Fleetwood Mac? No. I was always more comfortable in the band, although I've never turned anyone down. I think people have always thought of me as being a bit "out there" and were put of by that. Mick and I did do "Werewolves of London" for Warren Zevon (Excitable boy), which was great, because it turned out to be a big hit - but that's really my only session-playing claim to fame.

What changes have you noticed in your playing over the last ten years or so? I've realized how much I don't know! Learning to play is an ongoing thing. I don't practice as much as I should, but sometimes I sit down and play along with things. I'll never be a "master" of the instrument, but I've realized and accepted that. It's amazing, but I've actually met people - who shall remain nameless - who are convinced that there's nowhere else for me to go in terms of learning bass.

What styles of music do you find interesting? I've been listening to a lot of Little Feat lately; their accents and grooves are a different mindset, and I enjoy them a lot. I'm also trying to teach myself how to play the slap style of upright bass.

Where do you see yourself musically in ten years? Still playing, I hope. I don't know if Fleetwood Mac will still be around, but I'm sure Mick and I will still be around. I recently made an album with a great singer from Seattle named Linda Thomas; the record sold well, so we'll do another one next year. I hope to continue with that.

Are their any other musical styles or techniques you'd like to explore? I like to work on the upright these days, because I really love that sound and feel. Other than that, I'm quite happy providing support for others.

Thanks to Mari for posting this to the Ledge and to Anusha for sending it to us.

|

![Christine McVie - Christine Mcvie (reissue) [New CD] Reissue picture](/vintage/img/g/tm8AAOSwpQxgrse5/s-l225/Christine-McVie-Christine-Mcvie-reissue-New-CD-Rei.jpg)