Fleetwood Mac? Every time I hear one of their cuts on the radio, I find myself thinking they're friends of mine, and I don't even know them, a famous name-dropper like me. I never paid attention to who was in the band when I first heard cuts like ‘Albatross’ and ‘Green Manalishi’ on the radio. I think it was 1968, moving fast into 1969. Tiny Tim was waking up to find himself a giant. Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin had begun to blaze like the twin meteorites they were. The Big Pink album was getting Recognized. Johnny Cash was starting his comeback. Fleetwood Mac? I liked the name, classy as a Cadillac. They weren't selling too many records, but the street musicians in the Village were talking about them like they were pros. Three Ex-Members Of John Mayall's Band. Serious Artists. A Group To Be Respected. I listened to a Fleetwood Mac album. Bluesy. Smooth. Tasty. Haunting. They'd found some kind of new ground to break. I figured I'd hear from them again, but I didn't bother reading the album cover to learn who they were.

In the summer of '69, Bob Dylan played the Isle of Wight. I was working for the New York Post, but Bob needed a road manager. Besides, I was like his emissary to the Beatles. I'd just finished covering the benevolent monster that'd terrified America from an alfalfa field in Bethel, N.Y., meaning the half-million kids at the Woodstock Festival, and now maybe there 'd be another half-million on this inaccessible island of thatched roofs, roads designed for horses, ancient villages built when people were smaller and, though the place was famous as a summer resort, a climate so Victorian you could leave the butter out all night.

Bob'd brought his wife, Sara, and the promoters put us up in a restored 16th Century stone cottage near the island's crumbling chalk cliffs, where you didn't dare go walking. The cottage grounds, all within a walled compound, included lawns, gardens, a pool, a tennis court, a carriage house and a renovated barn, fixed up as a rehearsal studio by the Band before we got there. The Band was staying at a nearby hotel, but they showed up every day to practice with Bob. Soon, Mal Evans, the legendary Beatles road manager, was invited to join us. We needed the help. And after a few days George Harrison arrived with his wife, Pattie, and a dub of the Beatles' Abbey Road album, which'd just been mixed.

George played us the dub on a turntable run through an amp in the barn so we could all hear it at once, me, Bob, the Band plus Bert Block, once famous as a band-leader but on the Isle of Wight to accompany Bob and the Band as the co-manager who'd booked the date. We sat on the floor, grouped around the amp to listen. There wasn't too much comment afterwards, some praise from the guys in the Band, an enigmatic remark from Bob. The album was too much for me to digest on first listening, like all Beatles albums, bigger than life. It was so powerful my impulse reaction was to take it as a threat. Later, in the cottage, George started telling me how they recorded Abbey Road.

"’Soon King’," he said, "that's ooss doin' Fleetwood Mac."

Fleetwood Mac?

"Y'know," George said, "y'go into a studio and y'look for ways t'make it sound different and that day we said, 'OK, lads, today we're goin' t'be Fleetwood Mac.' Y'know, we did it the way they'd do it, only it was ooss."

A Group To Be Respected. The street musicians in the Village weren't the only ones to flash on Fleetwood Mac. George's told me the same story a half-dozen times since, so it must be true. I understood what he meant because I'd done the same thing sitting down to write a column on a deadline, saying to myself, "Today I'll play Pete Hamill." Or Murray Kempton. Or Jimmy Breslin. An easy way to a new perspective, a fresh approach.

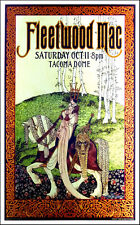

I've never kept up with Fleetwood Mac's personnel changes. I'd hear their new cuts on the radio, nothing that flipped me out, but there was always the germ of something new. Then, a couple of years ago, my oldest son, Myles, an art student, discovered a new group he liked. Fleetwood Mac. He'd been listening to the Fleetwood Mac album and he wanted it. Myles' tastes are pretty hip. ‘Over My Head’, ‘Rhiannon’, ‘Say You Love Me’ all became Top 10 singles off the Fleetwood Mac album, their first as far as Myles was concerned. Me, I liked those cuts, but I was wondering where the chicks came from. Fleetwood Mac never had any chicks. I ordered the album for Myles, then kept it for myself. By the time the Rumors album came out, I was just starting to get into the new Fleetwood Mac. Rumors was their best album yet, but the first few times I listened, I still thought it had cuts I could skip.

Then came Fleetwood Mac's Madison Square Garden concert in June of 1977, their first gala appearance in New York as superstars. I found myself begging for tickets. I got them. Onstage, Stevie Nicks was up tight with some vocal problems either because of a bad throat or the Big Apple'd caught in it. There were even a few numbers too studied to make grudging me want to boogy. But I left knowing the concert 'd got me off. Aftwards, I took two sisters, Joyce and Jane, to an intimate party for 1,000, thrown in honor of Fleetwood Mac by Warner Brothers Records at Les Mouches, a factory turned into a fancy disco on 11th Avenue, in the warehouse district. Nobody recognized me. I'd lost a ton of weight and I felt like the Invisible Man. People'd look right through me. I said hello to Ahmet Ertegun, chairman of the board of Atlantic Records, the smoothest operator in the music business and a buddy of mine for 16 years, but he didn't know who I was.

Out-of-towners, Joyce and Jane began cruising the party like a couple of hookers just in from Ohio on 46th Street. I found the buffet, dished myself up a plate and looked for an empty table. There was a darkened one over by the window wall, its centerpiece candle still unlit. I grabbed it, sat down and started eating, striking up a conversation with Nat Weiss, sitting at the table to my left. He was in the dumps about his love life and I invited him to Studio 54 afterwards with me, Joyce and Jane. He seemed interested. I didn't know anybody at the table to my right. Suddenly, Joyce and Jane came back to roost with me.

"Leave it to you to find the best table at the party," Joyce said. "Do you know who's sitting at the table next to you?" and she motioned toward the right.

"That's Fleetwood Mac."

In the dimness, I could make out Stevie Nicks, as dramatic in looks as in sound. I didn't recognize any of the others. I pulled out a ziploc bag containing a quarter of an ounce someone had laid on me and invited Joyce and Jane to stick their noses in. Joyce was determined New York'd remember her. Suddenly she leaned back and pushed her face into the conversation at Fleetwood Mac's table. I started necking with Jane. The next thing that happened was that Joyce got herself invited to sit at the Fleetwood Mac table.

"Do you mind?" she said.

I held up the ziploc bag. "Let's see what a good hustler you are," I told her. "Get them to invite us up to their hotel room and we'll give them some of this."

Joyce wasn't too hip. She didn't get the invitation to the hotel room, just a piece of paper with autographs from the whole band, plus a lighting man who wanted to sit with us. When she finally left town, I ended up with the autographs, but I still didn't know who was who in the band, except for Stevie Nicks. Wait'll their next album, I thought. The next album'll do it for them. A few months later and I discover that Rumors has sold more than seven million copies, one of the biggest albums in history. Not only that, but seven cuts off the album have turned out to be hit singles. I find myself loving every one of them.

Election Day '77 and ‘You Make Lovin' Fun’ is dazzling me from the dash, making me feel good, giving me a rush. I've got the volume up all the way. Suddenly, I'm at the toll booth of the Baltimore Harbor Tunnel with a sweet, pudgy girl in her 20s waiting for my 75 cents while she stands in her blue toll collector's uniform. Through my open window the sound of Fleetwood Mac tumbles out at her like a troupe of nutty passengers who are going to serenade her right there at the toll booth while she takes my dollar and gives me a quarter change. She smiles big. She's recognized the tune. She knows it's Fleetwood Mac. She knows it's ‘You Make Lovin' Fun’. Her smile gets bigger. She's already heard the record a thousand times and loved it that often. She feels like Fleetwood Mac are her buddies, too. She's bursting to laugh with happiness. She's bursting to tell me. Her smile gets even bigger. She's excited with the thrill of recognition, with knowing she and I have mutual friends, with my brimming joy and the reason for it. She wants to tell me how much she enjoys sharing this moment. But she doesn't say a word. The two of us are laughing out loud when I pull away. That's the kind of energy Fleetwood Mac radiates. Their records are bigger than life now.

The cheer they generate is contagious.

Election Day '77 and I want to vote for Fleetwood Mac. I want to vote for them because they've done something to turn on this barren world, something the politicians can't do. But they're not on the ballot. So instead I give them this printed applause.