|

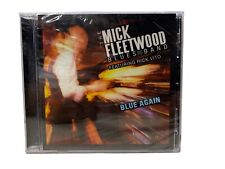

Blues To Salvation (Philadelphia Daily News) " Peter Green's turned up, like a bad penny," mused the voice on the other end of the Transatlantic phone line. And a rather sad, self-effacing and oft-befuddled voice it was, belonging to one of the more legendary and enigmatic personalities to ever emerge from the British blues rock scene. First with John Mayall's Bluesbreakers. Then with the original Fleetwood Mac, where he served as as author/performer of classics like "Black Magic Woman" (yeah, the Santana hit, too), "Oh Well" and "Green Manalishi." Long ago written off as an acid casualty - spoken of in the same breath as Pink Floyd's lost soul Syd Barrett and the Beach Boys' near basket case Brian Wilson - Peter Green is now enjoying (as best he can) one of the most unexpected comeback stories in music history. After 20 years of bouts with mental disease and hermitlike existence, this blues singer/guitarist has been pulled out of life's dust bin, cleaned up and restored to his job as functioning musician. Tonight, he'll be making his first Philadelphia appearance in literally decades at the Keswick Theater, sharing the bill with his one-time mentor John Mayall, and performing with his even older friend Nigel Watson and their band, dubbed Splinter Group. Peter Green is quick to acknowledge that he owes it all to the spirit of Robert Johnson, another haunted sufferer like himself, whose down-home, Devil-touched, moanin' country blues has pulled this singer/guitarist out of his lethargy, and become his ticket to ride with two super albums on the Snapper label. "Robert Johnson Songbook" was winner of the W.C. Handy Award for "Comeback Album of the Year" in 1998. This spring brought the even better release "Hotfoot Powder," which restores new life to the remaining Johnson compositions - including his best known material, actually. Helping out on the latter are the Splinter Group plus blues stalwarts Buddy Guy, Dr. John, Honeyboy Edwards, Otis Rush, Joe Louis Walker and Hubert Sumlin. The march to recovery actually began in 1995, when Peter Green moved in for a prolonged stay with his old high school band mate Watson. At the time, Green was clearly "a mess," relates his friend/supporter with a cheery tone, listening in on the extension and re-focusing the conversation whenever Green would lose his way. "His hair was all disheveled. His fingernails were long and curly, like you'd see on some holy man or beggar in Thailand. He'd long before taken a vow of poverty, and sworn to never play the guitar again," Watson says. "But one night I was playing some Robert Johnson blues in the kitchen, and the music so moved him that he asked to have his nails cut and reached for a guitar." What was it that touched Green and turned on his lights in Johnson songs like "Hell Hound On My Trail" and "Drunken Hearted Man," "From Four Until Late" and "Come On In My Kitchen" - all now brought to life again with stirring effect in Green's knowing, gritty, salt-of-the-earth interpretations? "The music seemed to be healing me. To copy what he was playing, to learn. . .he seemed to be hearing me," Green says in a halting fashion. "A lot of guys will say, 'Oh, he's alive in you when you're playing.' It was more than that. His music was me." Comparisons are something Peter Green has always lived with. He fought against the inevitable contrasts to Eric Clapton, the guitarist whom Green idolized and replaced in John Mayall's Bluesbreakers. And maybe the household name Green might be today, if he had been there first, he suggests. "The way John started with Eric, if he'd done that with me it would have been much easier for me," Green says. In fact, he did come into his own on Mayall's "The Hard Road" album and then in his breakoff group Fleetwood Mac, working in tandem with Mayall drummer Mick Fleetwood and bassist John McVie. Long before the likes of Lindsey Buckingham and Stevie Nicks converted them into a slick pop band, "the Mac" was a damned good British blues group - trading licks with some of Chicago's finest on the "Blues Jam at Chess" session and scoring hits with Green's signature song "Black Magic Woman," his epic, moody instrumental "Albatross," and classic "Green Manalishi," the latter suggesting anew that money was the root of all evil. Like many a musician who got caught up in the maelstrom of '60s freedom, fame and too much LSD, Green went off the deep end. While Jewish from birth, he took on the robes and trappings of a Christian pilgrim on stage, and argued with his Mac-mates that they should give all their money to charity to avoid the Devil's wrath. Eventually, he split from the group, to record one good solo album - ironically titled "The End of the Game" - then hang up his guitar and resume life as Peter Greenbaum (his original name). From time to time, there were rumors floating around that he'd been institutionalized, become a gravedigger, a bartender, a hospital orderly and a member of an Israeli commune. Yes, his songs would continue to be heard and earn royalties - with Santana's version of "Black Magic Woman" scoring a prestigious "Two Million Radio Plays" award from BMI. Yet Green says ambiguously, "I can't touch that money. It's nothing to me. I live on very meager wages. I don't need very much." As our conversation carried on, Green veered in and out of focus - rambling on in disjointed fashion about his induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame - "nearer to fun than misery," he cracked, or why he doesn't mix it up much on stage with Mayall the way "Eric would." Mayall does play harmonica on one tune with Green's group, Watson interjected, and Green often introduces Mayall, but they've only really jammed "once at the end of the British tour." When I asked him about his guitars, though, Peter Green got very focused, very clear and positive. Clearly the man is most comfortable when he's got an instrument in his mind and hands. And fortunately, he still wears them well.

|